- Research Article

- Open access

- Published:

New Limit Formulas for the Convolution of a Function with a Measure and Their Applications

Journal of Inequalities and Applications volume 2008, Article number: 748929 (2008)

Abstract

Asymptotic behavior of a convolution of a function with a measure is investigated. Our results give conditions which ensure that the exact rate of the convolution function can be determined using a positive weight function related to the given function and measure. Many earlier related results are included and generalized. Our new limit formulas are applicable to subexponential functions, to tail equivalent distributions, and to polynomial-type convolutions, among others.

1. Introduction

This paper investigates the existence of the limit of the ratio of a convolution and a positive valued weight function. The limit is given by an explicit formula in terms of the elements in the convolution and of the weight function. Our results are formulated for the convolution of a function with a measure and also for the convolution of two functions.

Our work was inspired by two different applications. One of them is the asymptotic stability theory of differential and integral equations, where an important question is to determine the exact convergence rate to the steady state. The second one is related to the asymptotic representation of the distribution of the sum of independent random variables. In the above and several similar problems, the weighted limits of convolutions play important role with different types of weights.

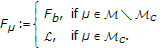

Let  be a given measure on the Borel sets of

be a given measure on the Borel sets of  and let

and let  be a measurable function. The convolution

be a measurable function. The convolution  is defined by

is defined by

for all  for which the integral exists.

for which the integral exists.

The convolution of two locally Lebesgue integrable functions  is defined by

is defined by

for  for which the integral exists.

for which the integral exists.

The motivation of our work came from the following three known results.

The first well-known result has been used frequently in the asymptotic theory of the solutions of differential and integral equations (see, e.g., [1]).

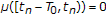

Theorem 1.1.

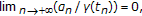

Let  be locally integrable and assume that

be locally integrable and assume that

Then

The next well-known simple result plays a central role, for instance, in the asymptotic theory of fractional differential and integral equations (see, e.g., [2–5])

Theorem 1.2.

Let  be given. Then

be given. Then

where  is the well-known Beta function.

is the well-known Beta function.

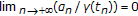

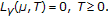

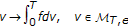

The third known result is formulated for continuous subexponential weight functions. A continuous function  is subexponential if

is subexponential if

The terminology is suggested by the fact that (1.7) implies that for every  .

.

The next result has been proved in [6] and it plays a central role to get exact rates of subexponential decay of solutions of Volterra integral and integro-differential equations (see, e.g., [6–8]).

Theorem 1.3.

Let the weight function  be continuous and subexponential. If

be continuous and subexponential. If  are continuous functions such that

are continuous functions such that

are finite, then

Based on the above three known results, we conclude the next observations.

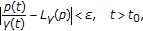

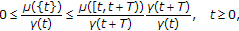

(i) All of the above theorems give different limit formulas for the ratio  at

at  . In fact

. In fact  in Theorem 1.1 and

in Theorem 1.1 and  , in Theorem 1.2.

, in Theorem 1.2.

(ii) The weight functions in Theorems 1.1 and 1.2 satisfy condition (1.7), but they do not satisfy condition (1.6).

(iii)The condition for  in (1.8) is not necessarily true in Theorem 1.1. Instead of that

in (1.8) is not necessarily true in Theorem 1.1. Instead of that  holds, where

holds, where  .

.

(iv) in Theorem 1.2 and at the same time

in Theorem 1.2 and at the same time  is not zero.

is not zero.

Our first goal is to prove results which unify the above-mentioned theorems. Second, we want to extend the limit formulas for the convolution of a function with a measure. This makes possible the applications of our theorems to not only density but also distribution functions.

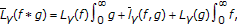

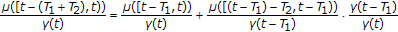

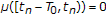

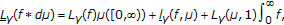

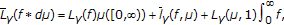

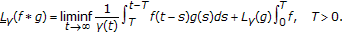

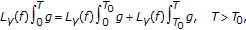

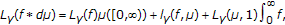

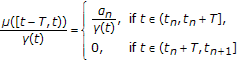

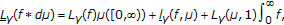

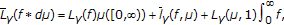

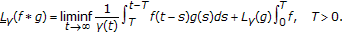

In fact we prove limit formulas which contain three terms, and the weight function does not satisfy condition (1.6). The major idea in the proofs of the main results is borrowed from the theory of subexponential functions. Namely, for large enough  , in fact

, in fact  the convolution

the convolution  can be split into three terms:

can be split into three terms:

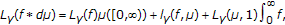

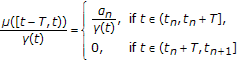

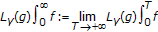

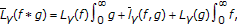

Under suitable assumptions and some time-tricky and technical treatments of the above three terms, we get the limit formula

where the following limits are finite:

In the limit formula (1.11), the terms  and

and  are interpreted as zero whenever

are interpreted as zero whenever  and

and  , respectively. So the values of

, respectively. So the values of  and

and  need not be finite in the applications.

need not be finite in the applications.

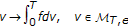

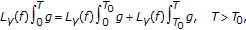

The limit formula (1.11) can be reformulated for the convolution of two functions  and

and  . Formally, it can be done if the measure

. Formally, it can be done if the measure  is such that

is such that  for every Borel set

for every Borel set  .

.

In that case  and

and  , where

, where

These indicate that our remarks (i)–(iv) are taking into account and the known Theorems 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 are unified in our results.

The organization of the paper is as follows. Section 2 contains notations and definitions. Section 3 lists and discusses the main results both for the convolution of a function with a measure and for the convolution of two functions. In Section 4 we present the corollaries of our main results for subexponential and long-tailed distributions. In Section 5 we show that our results can be easily reformulated to an extended set of weight functions. Section 6 gives some corollaries of our main results for the case when the weight function is of polynomial type. These results have possible applications in the asymptotic theory of fractional differential and integral equations. The proofs of the main results are given in Section 8 based on some preliminary statements stated and proved in Section 7.

2. The Basic Notations and Definitions

First we introduce some notations. The set of real numbers is denoted by  , and

, and  denotes the set of nonnegative numbers.

denotes the set of nonnegative numbers.

In our investigations we will make use of different sets of measures and functions given in the next definitions.

Definition 2.1.

Let  be the

be the  -algebra of the Borel sets of

-algebra of the Borel sets of  .

.  denotes the set of measures

denotes the set of measures  defined on

defined on  such that the

such that the  -measure of any compact subset of

-measure of any compact subset of  is a nonnegative number.

is a nonnegative number.

Note that the classical Lebesgue measure defined on  , denoted by

, denoted by  , is an element of

, is an element of  .

.

Let  . In this paper we will write

. In this paper we will write  for the

for the  -integral of

-integral of  on the closed interval

on the closed interval  . The

. The  -integral of

-integral of  on the interval

on the interval  is written as

is written as  When

When  , instead of

, instead of  we also write

we also write

Definition 2.2.

denotes the set of functions  which are Lebesgue integrable on any compact subset of

which are Lebesgue integrable on any compact subset of  . As usual,

. As usual,

Definition 2.3.

is the set of the Borel measurable functions  which are bounded on any compact subset of

which are bounded on any compact subset of

Definition 2.4.

A measure  from

from  belongs to the set

belongs to the set  if it is absolutely continuous with respect to

if it is absolutely continuous with respect to  . In this case

. In this case  means that

means that  is a nonnegative function from

is a nonnegative function from  such that

such that  for every

for every  (

( is the Radon-Nikodym derivative of

is the Radon-Nikodym derivative of  with respect to

with respect to  ).

).

It is not difficult to show that for any  and

and  the convolution

the convolution

of  and

and  is well defined on

is well defined on  . It is known (see, e.g., [9]) that for any

. It is known (see, e.g., [9]) that for any  the convolution

the convolution

of  and

and  is well defined for

is well defined for  almost every (shortly a.e.)

almost every (shortly a.e.)  . It follows that for any

. It follows that for any  and

and  the convolution

the convolution  is well defined for a.e.

is well defined for a.e.  and

and

where  .

.

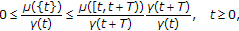

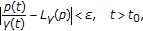

In this paper our major goal is to give conditions—possibly sharp—which guarantee the existence of the finite limit of the ratio

as  . The weight function

. The weight function  will belong to some special classes of the functions given in the following definitions.

will belong to some special classes of the functions given in the following definitions.

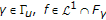

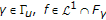

Definition 2.5.

Let  be the set of the functions

be the set of the functions  such that

such that

The set of the functions  for which the above convergence is uniform on any compact interval

for which the above convergence is uniform on any compact interval  is denoted by

is denoted by  .

.

It is clear that if  , then

, then

holds for  and hence it holds for any

and hence it holds for any  . Therefore for all

. Therefore for all  we have

we have

that is the function  is so called regularly varying at infinity. Thus applying the Karamata uniform convergence theorem (see, e.g., [10]) it follows that the convergence in (2.8) is uniform in

is so called regularly varying at infinity. Thus applying the Karamata uniform convergence theorem (see, e.g., [10]) it follows that the convergence in (2.8) is uniform in  on any compact set of

on any compact set of  assuming that

assuming that  is Lebesgue measurable. From this we get that the convergence in (2.6) is uniform on any compact set of

is Lebesgue measurable. From this we get that the convergence in (2.6) is uniform on any compact set of  assuming that

assuming that  is Lebesgue measurable. Thus

is Lebesgue measurable. Thus  contains the Lebesgue measurable members of

contains the Lebesgue measurable members of  On the other hand from [10] we know that there exists a nonmeasurable function

On the other hand from [10] we know that there exists a nonmeasurable function  such that

such that  and hence

and hence  is a proper subset of

is a proper subset of  .

.

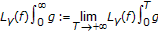

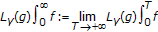

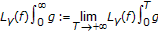

To give an explicit formula for the weighted limit of the convolution  at

at  we should assume some limit relations between

we should assume some limit relations between  and

and  and between

and between  and

and  .

.

Definition 2.6.

Let  .

.

(a) denotes the set of functions

denotes the set of functions  such that the limit

such that the limit

is finite.

(b) denotes the set of measures

denotes the set of measures  such that for any fixed

such that for any fixed  the limit

the limit

is finite.

-

(c)

Let

(2.11)

(2.11)

Definition 2.7.

Let  and

and  .

.  denotes the set of functions

denotes the set of functions  for which

for which

holds for any fixed

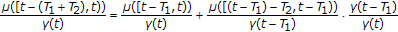

Remark 2.8.

A measure  belongs to

belongs to  if and only if for any fixed

if and only if for any fixed  the limit

the limit

is finite, where  . Moreover

. Moreover  for any

for any  It can be shown (see Proposition 7.3) that if

It can be shown (see Proposition 7.3) that if  and

and  then

then

We close this section with the following definition.

Definition 2.9.

A function  is said to be oscillatory on

is said to be oscillatory on  if there exist two sequences

if there exist two sequences  , such that

, such that  and

and  as

as  moreover

moreover  .

.

3. Main Results

In this section we state our main results. Their proofs are relegated to Section 8.

We use the following hypothesis.

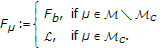

(H) , and the improper integral

, and the improper integral

is finite whenever  is oscillatory.

is oscillatory.

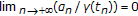

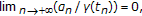

Note that if  then (H) is satisfied for any

then (H) is satisfied for any

In the next result we give an explicit limit formula for the weighted limit of the convolution of  and

and  at +

at +

Theorem 3.1.

Assume (H). Then the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following three statements are equivalent.

(a1) The limit

is finite.

(a2) For some  the limit

the limit

is finite.

(a3) The values

are finite, moreover

-

(b)

Assume that one of the statements

is true. Then the limit (3.3) is finite for any

is true. Then the limit (3.3) is finite for any  and

and  (3.6)

(3.6)

where

are finite.

Remark 3.2.

Our theorem is applicable for the case when  and also when

and also when  Namely, if

Namely, if  , then (3.7) yields that

, then (3.7) yields that  is zero independently on the value of

is zero independently on the value of  Similarly if

Similarly if  , then from (3.9) it follows that

, then from (3.9) it follows that  is independently zero on

is independently zero on  . We will see that this character of our theorem is important for getting limit formulas for polynomial-type convolutions (see Corollary 6.2 in Section 6).

. We will see that this character of our theorem is important for getting limit formulas for polynomial-type convolutions (see Corollary 6.2 in Section 6).

Now consider the case  that is,

that is,  . In this case we can apply Theorem 3.1 by using the hypothesis.

. In this case we can apply Theorem 3.1 by using the hypothesis.

, the function  is nonnegative such that

is nonnegative such that

is finite for every  , and the improper integral

, and the improper integral  is finite whenever

is finite whenever  is oscillatory

is oscillatory

Theorem 3.3.

Assume  . Then the following results hold.

. Then the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following three statements are equivalent.

(a1) The limit

is finite.

(a2) For some  the limit

the limit

is finite.

(a3) The values

are finite, moreover

-

(b)

Assume that one of the statements

is true. Then the limit (3.12) is finite for any

is true. Then the limit (3.12) is finite for any  , and

, and  (3.15)

(3.15)

where

are finite.

When  , then

, then  (see Proposition 7.3), and we get the following.

(see Proposition 7.3), and we get the following.

Theorem 3.4.

Let  , and assume that

, and assume that

(i) the improper integral

is finite, whenever  is oscillatory and

is oscillatory and  is not oscillatory;

is not oscillatory;

(ii)the improper integral

is finite, whenever  is not oscillatory and

is not oscillatory and  is oscillatory.

is oscillatory.

Then the statements of Theorem 3.3 are valid and (3.15) can be written in the form

Remark 3.5.

-

(a)

If

, and

, and  is nonnegative such that

is nonnegative such that  defined in (3.10) is finite for every

defined in (3.10) is finite for every  , then the conditions of Theorem 3.3 hold.

, then the conditions of Theorem 3.3 hold. -

(b)

If

, and

, and  , then Theorem 3.4 is applicable.

, then Theorem 3.4 is applicable.

Remark 3.6.

The well-known result Theorem 1.1 (see, e.g., [1]) is a straightforward consequence of Theorem 3.3.

4. Applications of The Main Results to Subexponential Functions

In this section we concentrate on the so-called subexponential functions which are strongly related to the subexponential distributions. Such distributions play an important role, for instance, in modeling heavy-tailed data. Such appears in the situations where some extremely large values occur in a sample compared to the mean size of data (see, e.g., [11] and the references therein).

First we consider the "density-type" subexponential functions.

Definition 4.1.

Assume that a function  is called subexponential if

is called subexponential if  and

and

Remark 4.2.

Let  such that

such that  is finite. Then

is finite. Then  is measurable and hence

is measurable and hence  . Thus

. Thus

which shows that

Therefore  and the normalized function

and the normalized function  is a subexponential density function. This gives the meaning of the "density-type" subexponentiality.

is a subexponential density function. This gives the meaning of the "density-type" subexponentiality.

From Theorems 3.4 and 6.1, we get the following.

Theorem 4.3.

If  is a subexponential function and

is a subexponential function and  , then

, then

It is worth to note that formula (4.4) has been obtained by Appleby et al. [7] in the case when the functions  and

and  are continuous on

are continuous on  . These types of limit formulas were used effectively for studying the subexponential rate of decay of solutions of integral and integro-differential equations (see, e.g., [6, 12]).

. These types of limit formulas were used effectively for studying the subexponential rate of decay of solutions of integral and integro-differential equations (see, e.g., [6, 12]).

Now we apply our main results to subexponential and long-tailed-type distribution functions.

Definition 4.4.

Let  be a distribution function on

be a distribution function on  such that

such that  and

and  for all

for all  . Then

. Then

(a) is called subexponential if

is called subexponential if

or equivalently

where  denotes the tail of

denotes the tail of  , that is,

, that is,

(b) is called long-tailed if

is called long-tailed if

The definition of the subexponential distribution was introduced by Chistyakov [13] in 1964 and there are a large number of papers in the literature dealing with them. For the major properties and also for applications, we refer to the nice introduction and review paper by Goldie and Klüppelberg [11] and the references in it.

Now we show the consequences of our main results for the above-defined class of distribution functions. The proofs will be explained in Section 8.

It is noted in [14, 15] (see also [11]) that the set of the subexponential distributions is a proper subset of the set of the long-tailed distributions.

In the first theorem, we give equivalent statements for subexponential distributions; and in the second one, we give a limit formula for the more general long-tailed distributions.

Theorem 4.5.

Let  be a distribution function such that

be a distribution function such that  and

and  . Then the following statements are equivalent.

. Then the following statements are equivalent.

(a) is subexponential.

is subexponential.

(b) is long-tailed and there is a

is long-tailed and there is a  such that the limit

such that the limit

is finite and

(c) is long-tailed and there is a

is long-tailed and there is a  such that

such that

is finite and

Theorem 4.6.

Let  be distribution functions,

be distribution functions,  , and

, and  is long-tailed. If

is long-tailed. If

are finite, and

then

The above theorem can be easily applied for tail-equivalent distributions defined as follows (see [11]).

Definition 4.7 (tail-equivalence).

Two distributions  with the conditions

with the conditions  and

and  are called tail-equivalent if

are called tail-equivalent if  is a positive number.

is a positive number.

Corollary 4.8.

Let  be distribution functions,

be distribution functions,  , and

, and  is long-tailed. If the conditions of Theorem 4.6 are satisfied, then

is long-tailed. If the conditions of Theorem 4.6 are satisfied, then  and

and  are tail equivalent if and only if

are tail equivalent if and only if  , that is, at least one of the distribution functions

, that is, at least one of the distribution functions  and

and  is tail equivalent to

is tail equivalent to  .

.

5. Further Corollaries for an Extended Set of Weight Functions

First we consider the extension of the set

Definition 5.1.

Let  . By

. By  one denotes the set of the functions

one denotes the set of the functions  such that

such that

for all  . By

. By  one denotes the set of the functions

one denotes the set of the functions  for which the convergence in (5.1) is uniform on

for which the convergence in (5.1) is uniform on  , for any

, for any  .

.

Remark 5.2.

It is clear that  , and

, and  if and only if

if and only if  , where

, where  is defined by

is defined by  .

.

Let  , and

, and  . Then

. Then

where  , and

, and  for

for  .

.

Thus our earlier results are applicable if  and

and  But from Remark 5.2 we have that

But from Remark 5.2 we have that  if and only if

if and only if  Moreover,

Moreover,  if and only if the limit

if and only if the limit

is finite for any

Remark 5.3.

if and only if  . Namely, let

. Namely, let  . Thus

. Thus  , and hence

, and hence  Now let

Now let  . Then

. Then  for any

for any  such that

such that  . Therefore

. Therefore

-almost every

-almost every  and hence

and hence  . From this it follows that

. From this it follows that  is absolute continuous with respect to

is absolute continuous with respect to  , that is,

, that is,  .

.

It can be seen that  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

Remark 5.4.

if and only if  . Here

. Here  denotes the set of functions

denotes the set of functions  for which

for which

for any

The above remarks show that our main results, Theorems 3.1–3.4, can be easily reformulated for the class  , assuming that we replace the hypotheses (H) and

, assuming that we replace the hypotheses (H) and  by

by  and

and  , respectively. In fact we use the following modified hypotheses.

, respectively. In fact we use the following modified hypotheses.

are such that

are such that  defined in (5.3) is finite for any

defined in (5.3) is finite for any  and the improper integral

and the improper integral

is finite, whenever  is oscillatory.

is oscillatory.

is nonnegative such that

is nonnegative such that

is finite for every  , and the improper integral

, and the improper integral  is finite, whenever

is finite, whenever  is oscillatory.

is oscillatory.

The extended form of Theorem 3.1 is as follows.

Theorem 5.5.

Assume  . Then the following results hold.

. Then the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following three statements are equivalent.

The limit

is finite.

For some  the limit

the limit

is finite.

The values

are finite, moreover

-

(b)

Assume that one of the statements

is true. Then the limit (5.8) is finite for any

is true. Then the limit (5.8) is finite for any  and

and  (5.11)

(5.11)

where

and  , defined in (3.8), are finite.

, defined in (3.8), are finite.

The extensions of Theorems 3.3 and 3.4 are similar and are left to the reader.

6. Power-Type Weight Function and The Role of The Middle Term

The introduction of our middle term was motivated by two independent papers [2, 4]. In both papers power-type estimations have been proved for the solutions of functional differential equations and of the wave equations with boundary condition, respectively. The joint idea was to transform the original problems into a convolution-type form. By treating the convolution form, power-type estimations were given without investigating any limit formula.

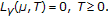

As a consequence of Theorem 3.4, we prove the next result, and as a corollary of it we give a power-type limit formula.

Theorem 6.1.

Let  , and let

, and let  be positive such that the limit

be positive such that the limit  is finite. If

is finite. If  and

and  , then the limit

, then the limit  is finite and

is finite and

where

and  , defined in (3.16), are finite.

, defined in (3.16), are finite.

The following corollary is a generalization of Theorem 1.2 and shows the importance of our middle term when  is a power-type function.

is a power-type function.

Corollary 6.2.

Let  and assume that the limits

and assume that the limits

are finite, where  are given constants. Then

are given constants. Then

where  is the Beta function, that is,

is the Beta function, that is,  (

( is the well-known Gamma function).

is the well-known Gamma function).

In the above limit formula,  and the middle term

and the middle term  whenever

whenever  .

.

7. Preliminary Results

In this section we state and prove preliminary and auxiliary results. They will be used in the proofs of our main results in the next section.  denotes the set of the positive integers.

denotes the set of the positive integers.

Proposition 7.1.

Let  and

and  such that

such that  is finite for any

is finite for any  with a fixed

with a fixed  Then

Then  .

.

Proof.

Let  and

and  such that

such that  . Then

. Then

and this yields  .

.

Proposition 7.2.

Let  and

and  . Then the following hold.

. Then the following hold.

(a) for any

for any  .

.

(b) where

where  is the only element of the set

is the only element of the set  .

.

Proof.

-

(a)

First we show that

is additive. In fact for

is additive. In fact for  we have

we have  (7.2)

(7.2)

for  . This yields

. This yields  . Therefore

. Therefore  can be extended in a unique way to

can be extended in a unique way to  such that it is additive. Now (a) follows since

such that it is additive. Now (a) follows since  is nonnegative on

is nonnegative on  .

.

-

(b)

For any

we have

we have  (7.3)

(7.3)

therefore

Since  is arbitrarily chosen, statement (b) is proved.

is arbitrarily chosen, statement (b) is proved.

Proposition 7.3.

Let  and assume that

and assume that  , that is,

, that is,  . If

. If  then

then

Proof.

is a positive function, therefore  Thus for any

Thus for any  there exists a

there exists a  such that

such that

From this it follows that

On the other hand there is a  such that

such that

where we used that  .

.

Thus

therefore

From this it follows

for any fixed  . This completes the proof as

. This completes the proof as  .

.

Definition 7.4.

For any  and

and  , let

, let  be defined by

be defined by

It is clear that for any fixed  is a measure on

is a measure on  (the unit mass at

(the unit mass at  ), and

), and  .

.

Proposition 7.5.

Let  be a given sequence in

be a given sequence in  such that

such that

and let  be a sequence of nonnegative numbers. Suppose

be a sequence of nonnegative numbers. Suppose  .

.

-

(a)

If the measure

belongs to

belongs to  then

then  and

and

-

(b)

If

and

and  then

then

Proof.

It is clear that

-

(a)

Let

be fixed. Since

be fixed. Since  for every

for every  we have

we have  (7.13)

(7.13)

and hence  This and statement (a) of Proposition 7.2 imply that

This and statement (a) of Proposition 7.2 imply that  Therefore

Therefore

But  and hence statement (a) is proved.

and hence statement (a) is proved.

-

(b)

Let

and

and  be fixed. Then

be fixed. Then  (7.15)

(7.15)

for  Thus

Thus

for  But

But  and

and  therefore

therefore

The proof is complete.

Definition 7.6.

Let  be fixed.

be fixed.

-

(a)

denotes the

-algebra of the Borel sets of

-algebra of the Borel sets of

-

(b)

denotes the set of the finite measures on

.

. -

(c)

A topology defined on

is said to be the weak topology on

is said to be the weak topology on  if it is the weakest one which makes the mapping

if it is the weakest one which makes the mapping  (7.18)

(7.18)

continuous for all continuous  .

.

Definition 7.7.

For a fixed  and

and  , define the shift operator

, define the shift operator

Let  . For

. For

Proposition 7.8.

Let  , and

, and  be fixed. Then

be fixed. Then

where the convergence is in the weak topology of  .

.

Proof.

We should prove that for any fixed continuous function  , we have

, we have

For any  the function

the function  denotes the characteristic function of

denotes the characteristic function of

Let

where  and

and

Then from the statement (b) of Proposition 7.2, it follows

It is known that for a fixed continuous function  , there exists a sequence of step functions

, there exists a sequence of step functions  such that it converges to

such that it converges to  uniformly on

uniformly on  Thus for arbitrarily fixed

Thus for arbitrarily fixed  there is an index

there is an index  such that

such that

In that case

for all  large enough. Here we used the conclusion of the first part of our proof and statement (b) of Proposition 7.2. Since

large enough. Here we used the conclusion of the first part of our proof and statement (b) of Proposition 7.2. Since  is fixed but arbitrary, the proof is complete.

is fixed but arbitrary, the proof is complete.

Corollary 7.9.

Let  and

and  .

.

(a)If  is Borel measurable and Riemann integrable on any interval

is Borel measurable and Riemann integrable on any interval  , then

, then  .

.

(b) If  and

and  , then

, then  .

.

(c)Let  . If

. If  and

and  , then

, then  .

.

Proof.

From Proposition 7.8, it follows (see, e.g., [12]) that if  is

is  -a.e. continuous, then

-a.e. continuous, then  From this we get statements (a) and (b).

From this we get statements (a) and (b).

-

(c)

Let

and

and  be fixed. Since

be fixed. Since  , there is a

, there is a  such that

such that  (7.27)

(7.27)

and hence

Since  there is a

there is a  such that

such that

Thus

From the general transformation theorem for integrals (see, e.g., [12]) and from the translation invariance of the Lebesgue measure  , we get: for any

, we get: for any  and

and

But Proposition 7.3 shows that  and

and  So

So

Since  is arbitrary, this completes the proof.

is arbitrary, this completes the proof.

Proposition 7.10.

Let  , and assume that

, and assume that  is not oscillatory on

is not oscillatory on  . Then the following mappings have limits in

. Then the following mappings have limits in  as

as  :

:

Proof.

Let  be nonnegative on

be nonnegative on  , where

, where  is large enough. Then for

is large enough. Then for  and

and  , we get

, we get

Thus the above-defined mappings are decreasing, and hence their limits exist in  as

as  . When

. When  is eventually nonpositive, then the above procedure can be applied for

is eventually nonpositive, then the above procedure can be applied for  The proof is complete.

The proof is complete.

In the next two results, we give explicit formulas for the limit inferior and limit superior of the weighted convolution of  and

and  at

at

Theorem 7.11.

Assume (H). Then the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following two statements are equivalent.

The limit inferior

is finite.

For some  , the limit inferior

, the limit inferior

is finite.

-

(b)

If the limit inferior (7.36) is finite for a fixed

, then it is finite for any

, then it is finite for any  and

and  (7.37)

(7.37)

where

and  (they are defined in (3.7) and (3.9), resp.) are finite.

(they are defined in (3.7) and (3.9), resp.) are finite.

Proof.

Let  be fixed. Then for any

be fixed. Then for any  and

and  we get

we get

First we show that

In fact for  and

and  we have

we have

But  therefore for

therefore for  there exists

there exists  such that

such that

Thus (7.41) yields

and hence

which implies (7.40).

Since  we have

we have

Assume that  holds. Then (7.39), (7.40), and (7.45) imply

holds. Then (7.39), (7.40), and (7.45) imply  . On the other hand, from (7.39), (7.40), and (7.45) we get that

. On the other hand, from (7.39), (7.40), and (7.45) we get that  yields

yields  , and hence statement (a) is proved. This also verifies the first part of statement (b).

, and hence statement (a) is proved. This also verifies the first part of statement (b).

Now we prove the second part of statement (b). Assume that (7.36) is finite for any  . Then (7.39) yields

. Then (7.39) yields

Now assume that  is not oscillatory. Then there exists

is not oscillatory. Then there exists  such that either

such that either  for every

for every  or

or  for every

for every  . We consider the case when

. We consider the case when  for

for  , the other case can be handled similarly.

, the other case can be handled similarly.

All the three terms on the right-hand side of (7.46) have limit as  in

in  In fact

In fact

and by Proposition 7.10, we get

moreover

Now the second part of (b) is proved, since the left-hand side of (7.46) is finite and independent on  .

.

Now assume that  is oscillatory on

is oscillatory on  and as we assumed

and as we assumed  is finite. In that case

is finite. In that case  and hence

and hence

Thus by using similar arguments to those we used above, statement (b) is proved again.

Theorem 7.12.

Assume (H). Then the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following two statements are equivalent.

The limit superior

is finite.

For some  the limit superior

the limit superior

is finite

-

(b)

If the limit superior (7.52) is finite for a fixed

then it is finite for any

then it is finite for any  and

and  (7.53)

(7.53)

where

and  (they are defined in (3.7) and (3.9), resp.) are finite.

(they are defined in (3.7) and (3.9), resp.) are finite.

Proof.

Its proof is similar to the proof of Theorem 7.11, therefore it is omitted.

Theorem 7.13.

Let  , and assume that

, and assume that

-

(i)

the improper integral

(7.55)

(7.55)

is finite, whenever  is oscillatory and

is oscillatory and  is not oscillatory,

is not oscillatory,

-

(ii)

the improper integral

(7.56)

(7.56)

is finite, whenever  is not oscillatory and

is not oscillatory and  is oscillatory.

is oscillatory.

Then the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following two statements are equivalent.

The limit inferior

is finite.

For some  the limit inferior

the limit inferior

is finite.

-

(b)

If the limit inferior (7.58) is finite for a fixed

, then it is finite for any

, then it is finite for any  and

and  (7.59)

(7.59)

where

and  (they are defined in Theorem 3.3) are finite.

(they are defined in Theorem 3.3) are finite.

Proof.

Let  be fixed. Then for each

be fixed. Then for each  and

and  , we have

, we have

The proof of (7.40) can easily be modified to show that

Since

it follows from (7.62) that

By using (7.61), (7.62), and (7.64) instead of (7.39), (7.40), and (7.45), the argument employed in the proof of Theorem 7.11(a) and the first part of (b) extends to give (a) and the first part of (b).

Consider now the proof of (7.59). Suppose that (7.58) is finite for every  . By (7.61),

. By (7.61),

for each  . We separate the proof into four steps.

. We separate the proof into four steps.

-

(h)

Suppose first that

and

and  are oscillatory. Then

are oscillatory. Then  , hence (7.65) implies that

, hence (7.65) implies that  (7.66)

(7.66)

It now follows that  is finite and

is finite and

-

(j)

Suppose next that exactly one of the functions

and

and  is oscillatory. Without loss of generality, we can assume that

is oscillatory. Without loss of generality, we can assume that  is oscillatory and

is oscillatory and  is not oscillatory. Then

is not oscillatory. Then  , hence (7.65) shows that

, hence (7.65) shows that  (7.68)

(7.68)

By (i),  is finite and

is finite and

-

(k)

Suppose that there is

such that

such that  and

and  for every

for every  . Then it follows from

. Then it follows from  and

and  (7.70)

(7.70)

that

A similar argument gives that

Since

we have

Using (7.65), we deduce from (7.71), (7.72), and (7.74) that the limits in (7.71) and (7.72) are finite, and therefore  exists and is finite. This gives (7.59). If

exists and is finite. This gives (7.59). If  and

and  for every

for every  , then a similar proof can be applied.

, then a similar proof can be applied.

-

(l)

Suppose finally that there is

such that

such that  and

and  for every

for every  , or

, or  and

and  for every

for every  . This case follows by an argument entirely similar to that for the case (k). Here the limits (7.71) and (7.72) are in

. This case follows by an argument entirely similar to that for the case (k). Here the limits (7.71) and (7.72) are in  , and (7.74) is nonpositive.

, and (7.74) is nonpositive.

Theorem 7.14.

Under the hypotheses of Theorem 7.13 the following results hold.

-

(a)

The following two statements are equivalent.

The limit superior

is finite.

For some  , the limit superior

, the limit superior

is finite.

-

(b)

If the limit superior (7.76) is finite for a fixed

, then it is finite for any

, then it is finite for any  and

and  (7.77)

(7.77)

where

and  (they are defined in Theorem 3.3) are finite.

(they are defined in Theorem 3.3) are finite.

Proof.

The proof is similar to the proof of the previous theorem, therefore it is omitted.

8. The Proofs of The Main Results

In this section, we give the proofs of the results stated in Sections 3–6.

Proof of Theorem 3.1.

A similar argument employed in the proof of Theorem 7.11 gives the equivalence of  and

and  , and part (b). It is clear from

, and part (b). It is clear from  and (b) that

and (b) that  implies

implies  . If

. If  holds, then by Theorems 7.11 and 7.12, the values of

holds, then by Theorems 7.11 and 7.12, the values of  and

and  are finite. Since

are finite. Since  , it follows from (7.37) and (7.53) that

, it follows from (7.37) and (7.53) that  . This shows that

. This shows that  yields

yields  .

.

Proof of Theorem 3.3.

This is an immediate consequence of Theorem 3.1.

Proof of Theorem 3.4.

The argument of Theorem 7.13 can easily be generalized to prove the equivalence of  and

and  , and part (b).

, and part (b).  and (b) imply

and (b) imply  . If

. If  holds, then we can apply Theorems 7.13 and 7.14. It now follows from (7.59) and (7.77) that

holds, then we can apply Theorems 7.13 and 7.14. It now follows from (7.59) and (7.77) that  , and therefore

, and therefore  is satisfied.

is satisfied.

Proof of Theorem 1.1.

First we suppose that  is nonnegative. It follows from

is nonnegative. It follows from  that

that

for every  . We can see that the hypothesis

. We can see that the hypothesis  is satisfied with

is satisfied with  , and

, and  . This shows that Theorem 3.3 can be applied. Consider now the proof that

. This shows that Theorem 3.3 can be applied. Consider now the proof that  holds, and

holds, and  . There exists

. There exists  such that

such that

This implies that

hence

and therefore, by  ,

,

Since

it follows from (8.5) that  is true, and

is true, and  . Now (3.15) gives the result.

. Now (3.15) gives the result.

In the general case, the preceding can be applied to both  and

and  .

.

Proof of Theorem 4.3.

is a subexponential function, and therefore  and

and

Theorem 3.4 may now be applied with  , and

, and  is obtained. Thus the result follows from Theorem 6.1 with

is obtained. Thus the result follows from Theorem 6.1 with  .

.

Proof of Theorem 4.5.

Suppose that  is subexponential. Then

is subexponential. Then  is long-tailed as is well known (details can be found in [11]), and thus

is long-tailed as is well known (details can be found in [11]), and thus  . The distribution function

. The distribution function  generates a distribution

generates a distribution  . Since

. Since

we can see that  for every

for every  , and therefore

, and therefore  . It follows that the hypothesis (H) is satisfied with

. It follows that the hypothesis (H) is satisfied with  and

and  . This shows that Theorem 3.1 can be applied. Since

. This shows that Theorem 3.1 can be applied. Since  is subexponential, the equivalence of

is subexponential, the equivalence of  and

and  implies (4.9), and (3.6) gives (4.10). We have proved that (b) comes from (a). On the other hand, (c) obviously follows from (b).

implies (4.9), and (3.6) gives (4.10). We have proved that (b) comes from (a). On the other hand, (c) obviously follows from (b).

By the equivalence of  and

and  in Theorem 3.1, (c) implies (a).

in Theorem 3.1, (c) implies (a).

Proof of Theorem 4.6.

is long-tailed, hence  . The distribution function

. The distribution function  characterizes a distribution

characterizes a distribution  . Then

. Then

giving

and therefore  and

and  .

.

It follows that the condition (H) is satisfied with  and

and  .

.

According to Theorem 3.1 and (3.6), we now have

and (3.6), we now have

Applying this and taking into account Proposition 7.2(b), the result follows, since

Proof of Theorem 5.5.

By the correspondence between hypotheses (H) and (H( )), Theorem 3.1 implies the result.

)), Theorem 3.1 implies the result.

Proof of Theorem 6.1.

By Theorem 3.4, we deduce that

Let  . Since

. Since  and

and  , we can find

, we can find  such that

such that

and therefore also

This implies that

Equation (8.13) shows that  is finite, hence the definition of

is finite, hence the definition of  and the previous inequality give

and the previous inequality give

and therefore

The result now follows from Theorem 3.4 (see Theorem 3.3 ) by applying

) by applying

and  .

.

Proof of Corollary 6.2.

If

then  . Let

. Let  be defined by

be defined by

Then  , and therefore

, and therefore  . By (6.3) and Theorem 6.1, it is enough to prove

. By (6.3) and Theorem 6.1, it is enough to prove

which comes from the definition of the Beta function.

References

Gripenberg G, Londen S-O, Staffans O: Volterra Integral and Functional Equations, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications. Volume 34. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; 1990:xxii+701.

Cavalcanti MM, Guesmia A: General decay rates of solutions to a nonlinear wave equation with boundary condition of memory type. Differential and Integral Equations 2005,18(5):583–600.

Darwish MA, El-Bary AA: Existence of fractional integral equation with hysteresis. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2006,176(2):684–687. 10.1016/j.amc.2005.10.014

Furati KM, Tatar N-E: Power-type estimates for a nonlinear fractional differential equation. Nonlinear Analysis: Theory, Methods & Applications 2005,62(6):1025–1036. 10.1016/j.na.2005.04.010

Mydlarczyk W, Okrasiński W: A nonlinear system of Volterra integral equations with convolution kernels. Dynamic Systems and Applications 2005,14(1):111–120.

Appleby JAD, Reynolds DW: Subexponential solutions of linear integro-differential equations. In Dynamic Systems and Applications. Vol. 4. Dynamic, Atlanta, Ga, USA; 2004:488–494.

Appleby JAD, Győri I, Reynolds DW: On exact rates of decay of solutions of linear systems of Volterra equations with delay. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2006,320(1):56–77. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2005.06.103

Appleby JAD, Reynolds DW: Subexponential solutions of linear integro-differential equations and transient renewal equations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A 2002,132(3):521–543.

Hewitt E, Stromberg K: Real and Abstract Analysis: A Modern Treatment of the Theory of Functions of a Real Variable. Springer, New York, NY, USA; 1965.

Bingham NH, Goldie CM, Teugels JL: Regular Variation, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications. Volume 27. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK; 1987:xx+491.

Goldie CM, Klüppelberg C: Subexponential distributions. In A Practical Guide to Heavy Tails (Santa Barbara, CA, 1995). Birkhäuser, Boston, Mass, USA; 1998:435–459.

Bauer H: Measure and Integration Theory, de Gruyter Studies in Mathematics. Volume 26. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany; 2001:xvi+230.

Chistyakov VP: A theorem on sums of independent positive random variables and its applications to branching random processes. Theory of Probability and Its Applications 1964, 9: 640–648. 10.1137/1109088

Embrechts P, Goldie CM: On closure and factorization properties of subexponential and related distributions. Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society. Series A 1980,29(2):243–256. 10.1017/S1446788700021224

Pitman EJG: Subexponential distribution functions. Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society. Series A 1980,29(3):337–347. 10.1017/S1446788700021340

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by Hungarian National Foundation for Scientific Research Grant no. K73274.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Győri, I., Horváth, L. New Limit Formulas for the Convolution of a Function with a Measure and Their Applications. J Inequal Appl 2008, 748929 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/748929

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/748929

is true. Then the limit (3.3) is finite for any

is true. Then the limit (3.3) is finite for any  and

and

is true. Then the limit (3.12) is finite for any

is true. Then the limit (3.12) is finite for any  , and

, and

, and

, and  is nonnegative such that

is nonnegative such that  defined in (3.10) is finite for every

defined in (3.10) is finite for every  , then the conditions of Theorem 3.3 hold.

, then the conditions of Theorem 3.3 hold. , and

, and  , then Theorem 3.4 is applicable.

, then Theorem 3.4 is applicable. is true. Then the limit (5.8) is finite for any

is true. Then the limit (5.8) is finite for any  and

and

is additive. In fact for

is additive. In fact for  we have

we have

we have

we have

belongs to

belongs to  then

then  and

and

and

and  then

then

be fixed. Since

be fixed. Since  for every

for every  we have

we have

and

and  be fixed. Then

be fixed. Then

-algebra of the Borel sets of

-algebra of the Borel sets of

.

. is said to be the weak topology on

is said to be the weak topology on  if it is the weakest one which makes the mapping

if it is the weakest one which makes the mapping

and

and  be fixed. Since

be fixed. Since  , there is a

, there is a  such that

such that

, then it is finite for any

, then it is finite for any  and

and

then it is finite for any

then it is finite for any  and

and

, then it is finite for any

, then it is finite for any  and

and

and

and  are oscillatory. Then

are oscillatory. Then  , hence (7.65) implies that

, hence (7.65) implies that

and

and  is oscillatory. Without loss of generality, we can assume that

is oscillatory. Without loss of generality, we can assume that  is oscillatory and

is oscillatory and  is not oscillatory. Then

is not oscillatory. Then  , hence (7.65) shows that

, hence (7.65) shows that

such that

such that  and

and  for every

for every  . Then it follows from

. Then it follows from  and

and

such that

such that  and

and  for every

for every  , or

, or  and

and  for every

for every  . This case follows by an argument entirely similar to that for the case (k). Here the limits (7.71) and (7.72) are in

. This case follows by an argument entirely similar to that for the case (k). Here the limits (7.71) and (7.72) are in  , and (7.74) is nonpositive.

, and (7.74) is nonpositive. , then it is finite for any

, then it is finite for any  and

and